We were in Mopti for one reason and one reason only: Dogon. Our interest in the region began while in Dhakla, on the edge of Western Sahara, headed for Mauritania. We crossed paths with a fellow traveler planning to spend several weeks trekking throughout the region. He spoke of villages tucked deep within a network of canyons, unscathed by western civilization, where the people held tight to their religion and traditions. Naturally, we were intrigued.

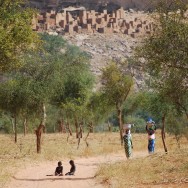

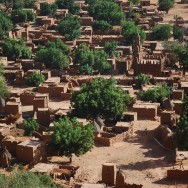

The Dogon people are best known for their mythology, mask dances, and unique architecture, all of which fascinated us. We met with at least seven guides while in Mali, and approached by a dozen others. It seems that everyone, and I do mean everyone, doubles as a guide – it was a lot to take in. Most do a three-day circuit, but as usual, we wanted to craft our own plan: something guides and tour operators just don’t seem to understand.

We spent several days staring at the same maps, repeating the same conversations, until we were blue in the face. Dogon was starting to lose its luster, when along came Gabriel: a young guide from the village of Nombori. He was personable, flexible, and came at a reasonable rate. We discussed doing an 8-day trek, covering roughly 160km. He seemed genuinely excited, so we settled on 4-days up front, with the option for more, and off we went.

Gabriel was in for a surprise. As it turns out, most people walk a few kilometers, take a three or four hour lunch break, walk a few more, and then call it a day around 3pm. Not us. We weren’t paying to twiddle our thumbs – we do enough of that as it is. We wanted to experience all that the region had to offer, even if it meant walking from sunrise to sunset in order to do it.

Sadly, by day two, we realized that our adventure wasn’t so adventurous anymore. The ‘Dogon’ we read about is a thing of the past. Time has a way of changing everything, regardless of location. Sure, you can still see masked dances, but their put on solely for tourists, and in my opinion the beauty is lost when it’s strictly for financial gain. Some still practice their animist faith, but for the most part, missionaries have made their mark on much of the territory and any ancient traditions take place behind closed doors.

It wasn’t a total wash, though. We spent starry nights sleeping on rooftops, helped local children gather firewood, and listened to Gabriel share his thoughts on children: the more the merrier, because they’re cheap. Cheap? This, coming from someone who just said he practically raised himself from age ten? I bit my tongue.

We landed in his village on Christmas day. Rich had the pleasure of attending a small church service and later that evening, I watched as the entire congregation gathered for a celebration of music and dancing. It was by far the most interesting and meaningful experience we had while in Dogon… if not Mali, for that matter.

We weren’t exactly giddy at the prospect of spending four more days, as previously discussed, so I played the Grinch and broke the news to Gabriel. The three of us sat there, side by side in silence, as he sulked. I went with the “we’re not feeling well” approach, because saying, “This is a tourist trap” or “We wanted history and interaction, but instead you would rather listen to my ipod and F-off with your buddies, while we melt… and pay you to do it”, just sounds rude. Besides, it wasn’t a complete fabrication. We had been feeling slightly under the weather for days, presumably due to our diet.

In the end, he chalked it up to be exhaustion. We laughed it off and tried to explain that if we were moving at our own pace, we would have been able to complete the entire stretch in five days with minimal effort. He said we were crazy, which might be true, but not for that statement. We agreed to disagree.